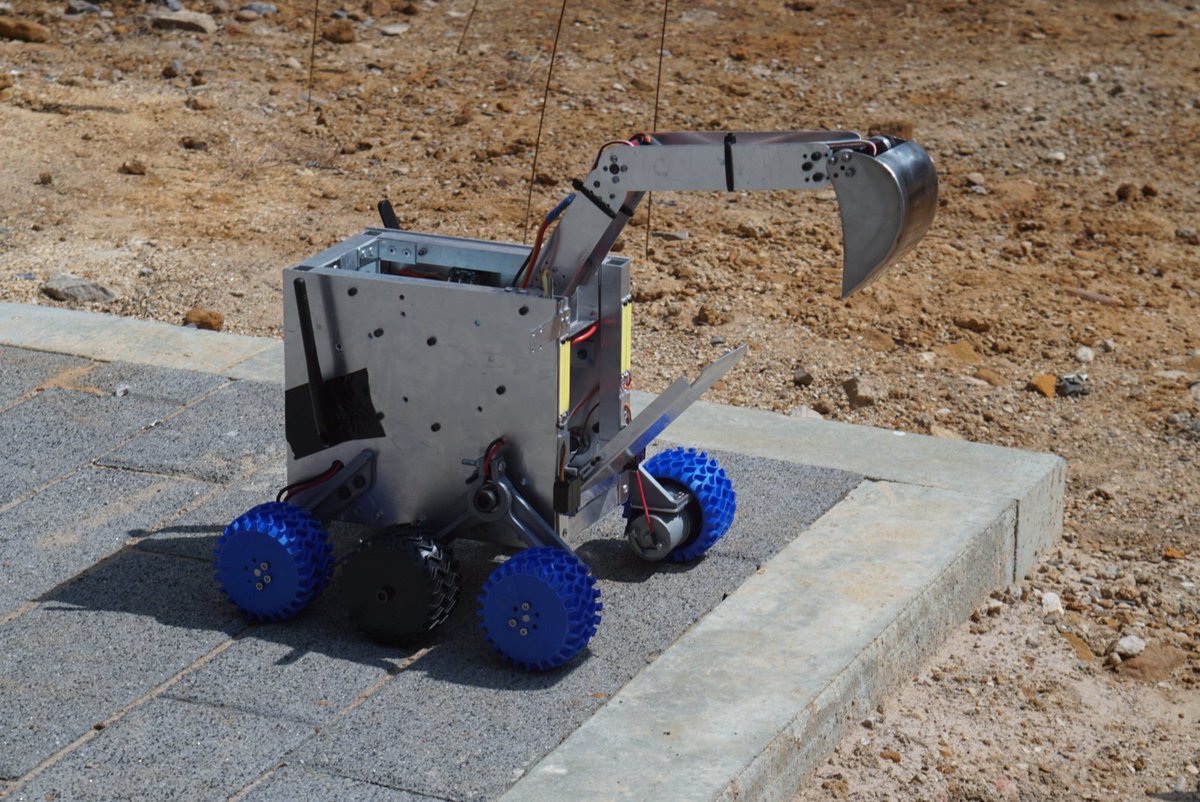

In the second year of my degree, I joined team Moonworks at The University of Sheffield to design, manufacture and test a small remotely operated lunar rover. This rover was developed to compete at the UK Students for the Exploration and Development of Space (UKSEDS) Lunar Rover competition 2018, held at the RAL Space centre in Oxford.

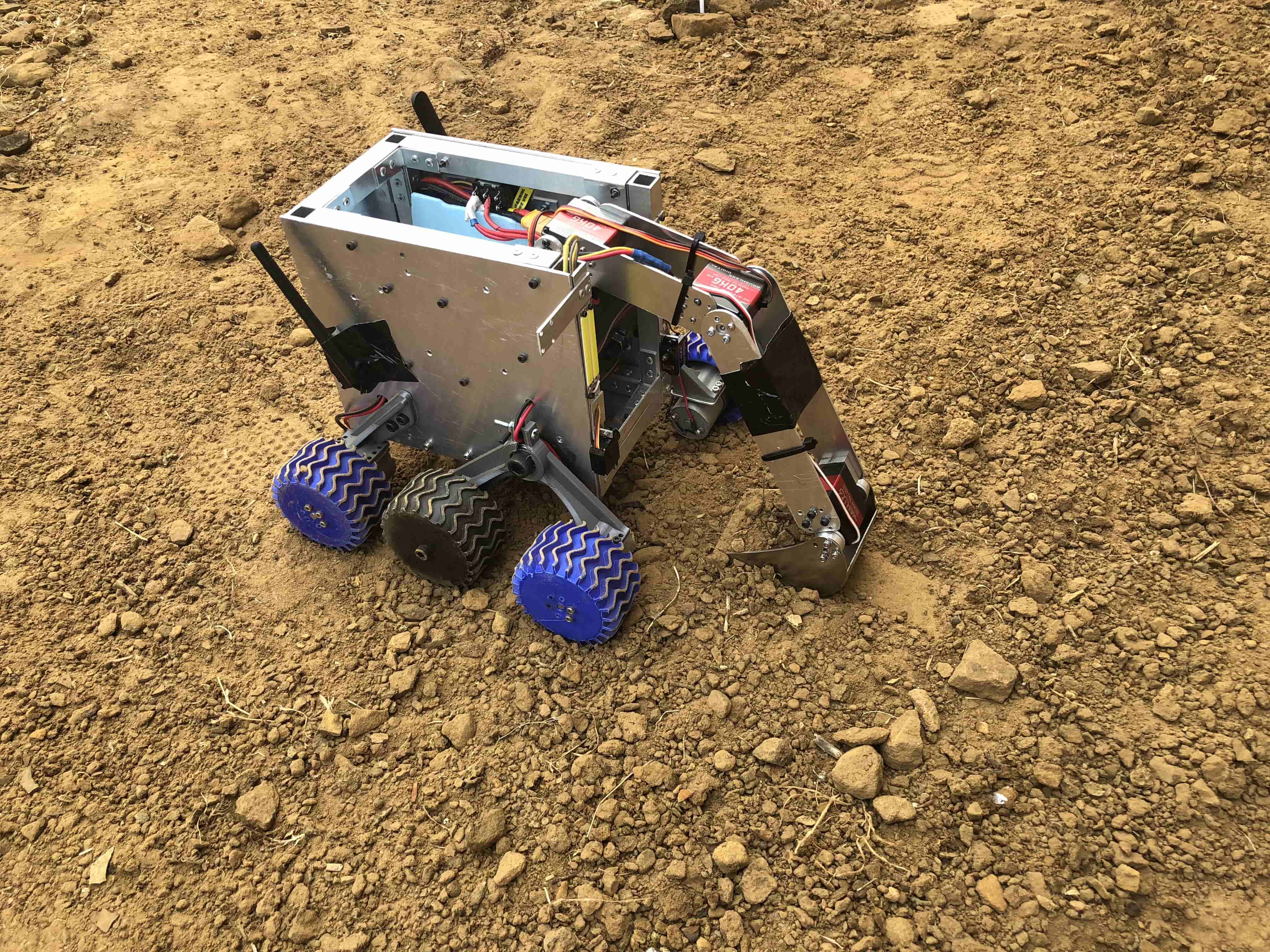

The rover was limited to a weight of 5kg, and had to fit within a 30cm cube, whilst be capable of travelling over a simulated rocky lunar terrain, with loose sand and large obstacles. The mission to complete at the competition was to drive into a crater, collect as much dry ice samples as possible, and return to base.

On the day of the competition, the entire rover was also subjected to vibration testing on a test bed at the space centre to prove that it would able to survive the violent forces involved with rocket launches.

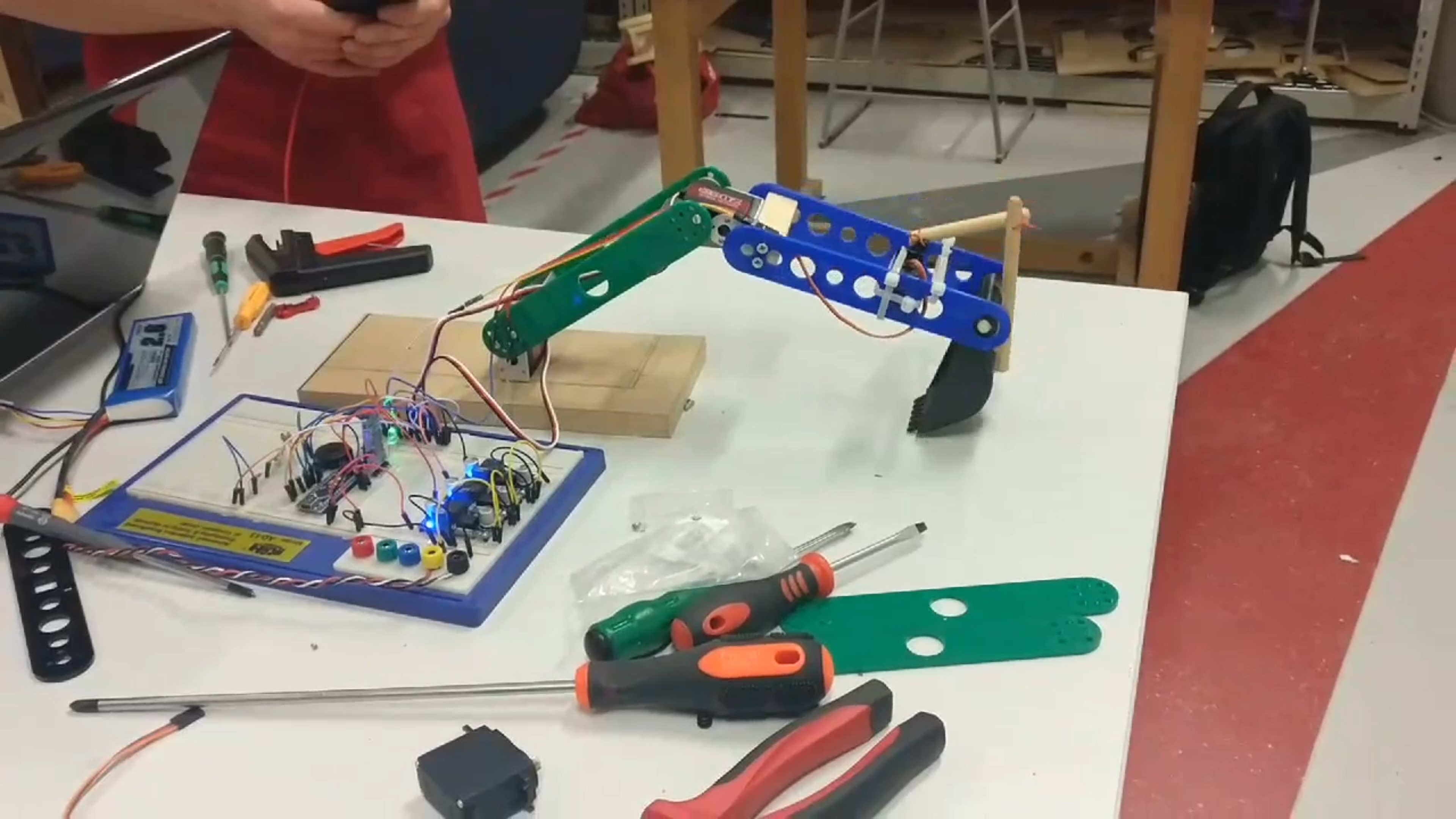

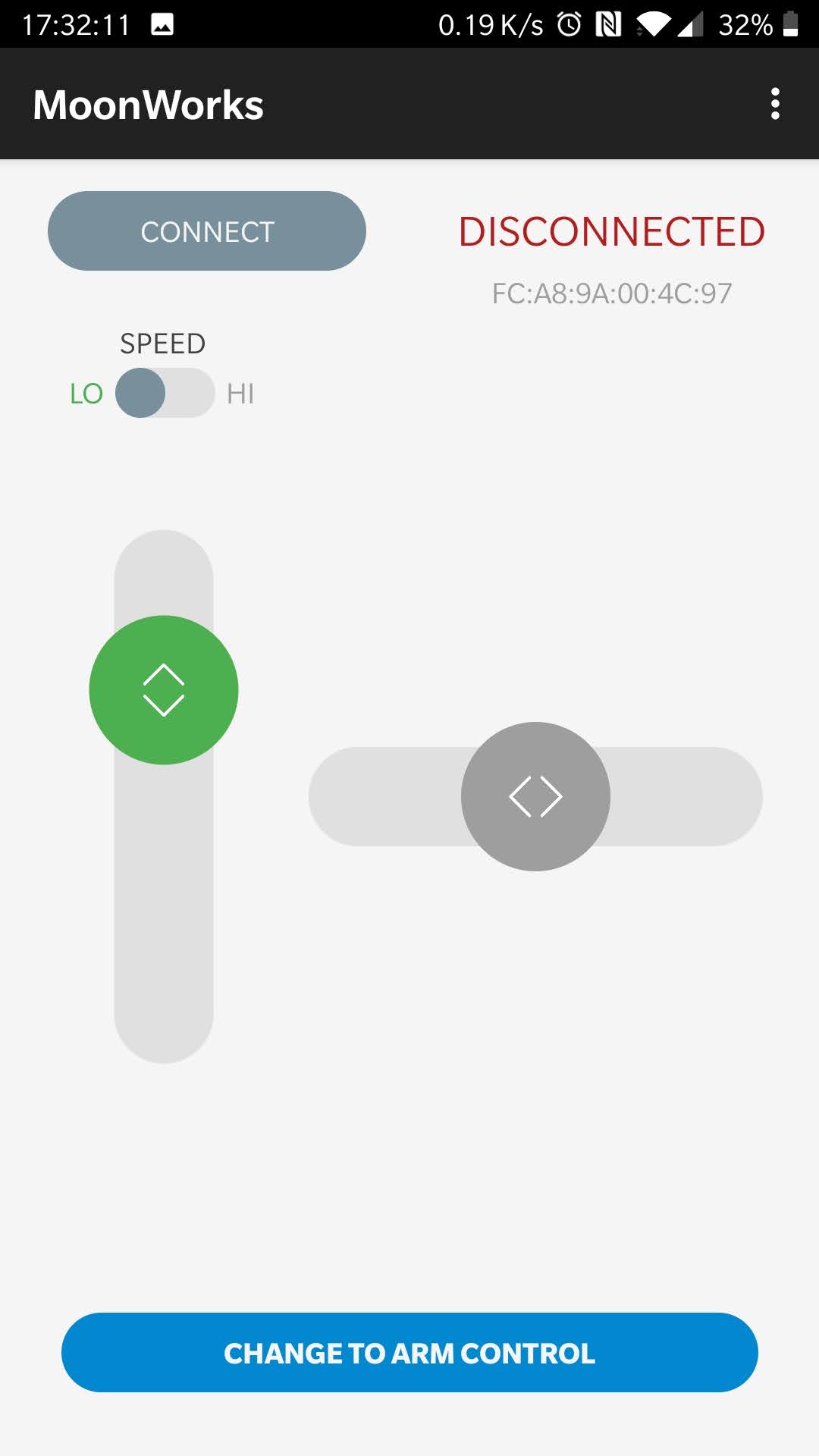

My contribution towards the project was the design of the robotic arm, responsible for picking up dry ice samples and moving them inside the rover’s sample containment area. I also developed an Android control application, that could connect to the rover via Bluetooth to control the locomotion system and the robot arm. This application was used during the development process to allow quick and easy testing of the rover, at a time when the main control system was not completed yet.

The 3-axis robot arm used high-torque (40 kg.cm) digital servo motors to rotate the two arm sections and the bucket, which were easily controlled by servo signals from an Arduino. The arm sections were made from 3mm water-jet aluminium, with their lengths calculated to let the arm reach anywhere in the required workspace, yet compact enough for the arm to fold into the rover’s chassis when not in use.

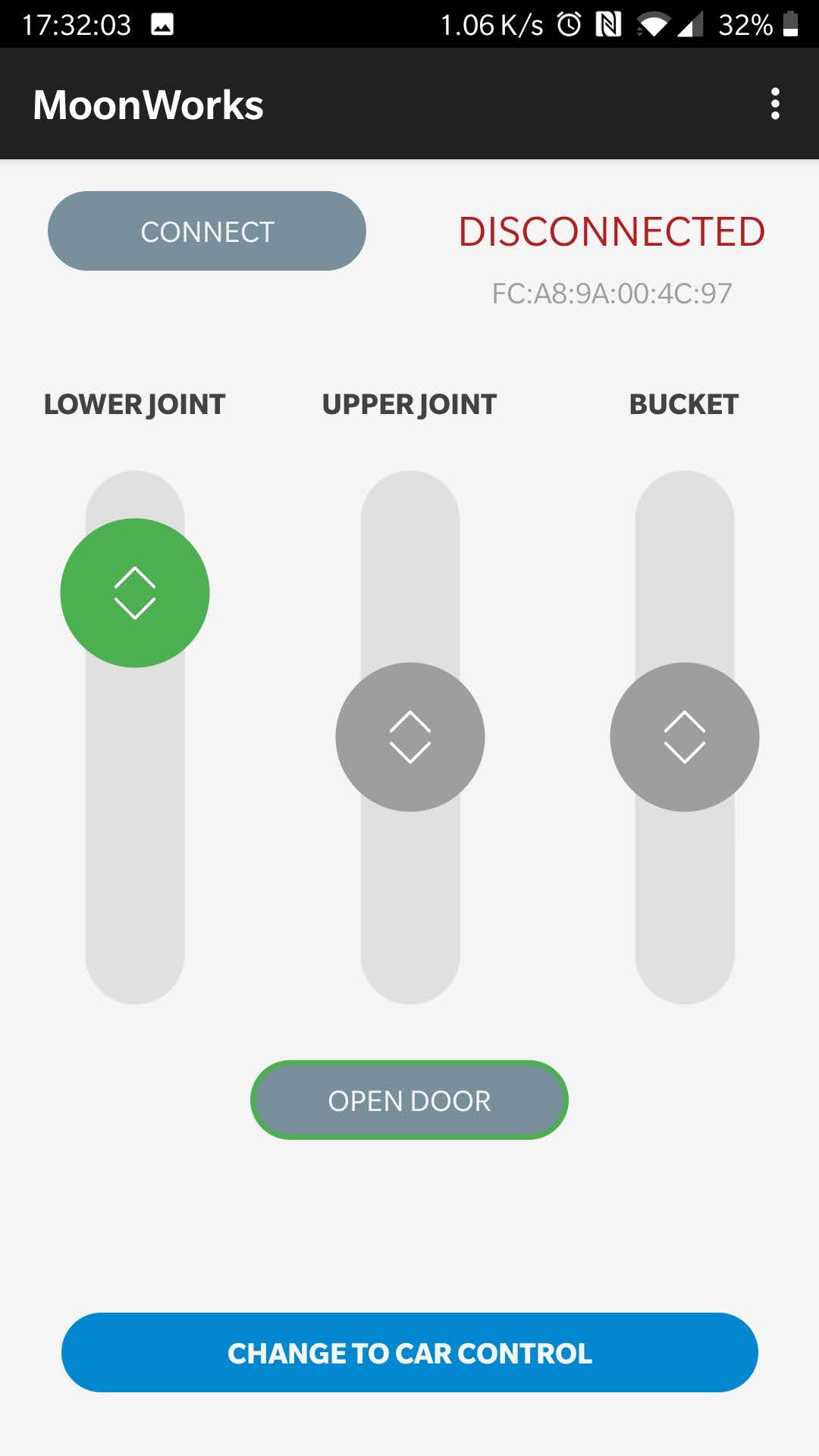

The Android application was simple and included two interfaces – one for controlling the rover’s locomotion system, and the second for controlling the robot arm axes. It communicated via Bluetooth to the rover’s electronics using a HC-05 Bluetooth receiver board, allowing the application to send serial commands.

The locomotion control interface contained two sliders, one for forward/backwards throttle, and another for left/right control. The rover’s wheels were fixed in position, so the on-board Arduino converted the throttle and steering inputs into tank-steer commands for the motor controllers. A convenient speed toggle was included to reduce the sensitivity of the controls where precise movements were needed.

The robot arm control interface contained 3 sliders, one for each servo on the robot arm, and a toggle button to open/close the sample containment door. Each slider controlled the speed the servos rotate (rather than their position) until they hit a software limit to prevent any collisions. Therefore, fine control over the arms position can be achieved by only moving the sliders a small amount in either direction.

When it came to attending the competition, we stayed up all night in our Travelodge hotel preparing the rover for the next morning. Somehow the custom motors drivers died during some pre-competition testing, so we rushed to hack together some h-bridge modules we had lying around to get the brushed motors up and running.

Despite getting almost no sleep, we made it to the RAL Space Centre on time. The event was really well organised, and throughout the day we got the chance to network with other teams, check out their rovers as well as some commercial ones, and speak to experienced industry members.

When it was our time slot to compete, we made our way to a patch of land outside the facility that had been transformed into a simulated lunar environment, with craters, sand, rocks and the dry ice samples. Our attempt at the course started well, with plenty of power from the brushed DC motors, and the control software/radio communications systems works perfectly. However, the terrain proved difficult to navigate, with the rover’s wheels being too small to overcome some of the larger rocks – although the power of the robot arm was used occasionally to lift the entire rover’s body over obstacles. To make matters worse, the vibration and forces on the wheels caused the tiny grub screws that clamp the wheels onto the motor shafts came loose, causing one of the wheels to detach from the rover. Ultimately, the rover failed to reach the crater where the dry ice samples were located, so we lost a lot of points for that reason.

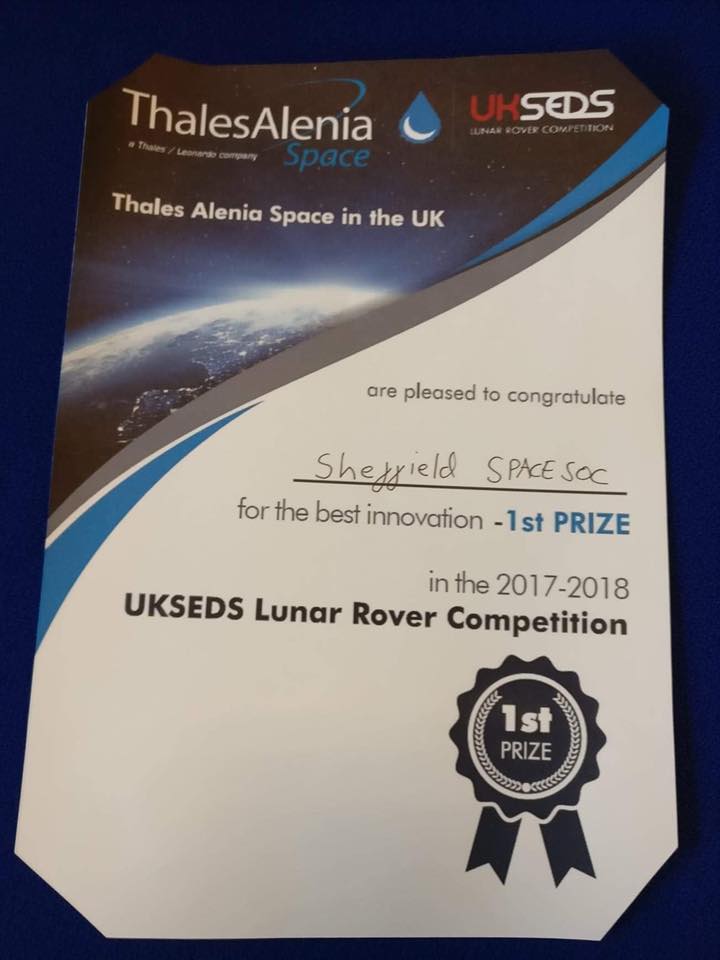

After an excessive amount of takeaway pizza for lunch, everyone gathered in the lobby to listen to a few presentations from industry members, before the final scores for each team were revealed. Despite our lack of samples collections, we managed to achieve 1st place for Best Innovation, for the robot arm design and the LabVIEW program used to operate the rover. We also came 2nd place for Best Outreach, and 2nd place for Best Critical Design Review (CDR).

Overall, this project was the first student led competition I contributed to during my degree, and became a stepping stone to being part of much larger projects later on.